What Causes Him to Be Able to Pray Again Rime of the Ancient Mariner

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (originally The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere ) is the longest major verse form past the English language poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the offset edition of Lyrical Ballads. Some modern editions use a revised version printed in 1817 that featured a gloss.[i] Along with other poems in Lyrical Ballads, information technology is frequently considered a point shift to modernistic poetry and the offset of British Romantic literature.[2]

The Rime of the Aboriginal Mariner recounts the experiences of a sailor who has returned from a long sea voyage. The mariner stops a man who is on his way to a wedding anniversary and begins to characterize a story. The Nuptials-Guest's reaction turns from bemusement to impatience to fearfulness to fascination as the mariner'due south story progresses, as can exist seen in the language style: Coleridge uses narrative techniques such every bit personification and repetition to create a sense of danger, the supernatural, or serenity, depending on the mood in dissimilar parts of the poem.

Synopsis [edit]

The poem begins with an onetime grey-bearded sailor, the Mariner, stopping a guest at a nuptials to tell him a story of a sailing voyage he took long ago. The Wedding-Guest is at first reluctant to heed, as the ceremony is almost to begin, merely the mariner's glittering center captivates him.

The mariner'southward tale begins with his transport parting on its journey. Despite initial skillful fortune, the ship is driven south past a storm and eventually reaches the icy waters of the Antarctic. An boundness appears and leads the ship out of the ice jam where it is stuck, but fifty-fifty as the boundness is fed and praised by the ship'southward crew, the mariner shoots the bird:

[...] With my cantankerous-bow

I shot the Albatross.[three]—lines 81–82

The crew is aroused with the mariner, assertive the albatross brought the due south wind that led them out of the Antarctic. Notwithstanding, the sailors change their minds when the weather becomes warmer and the mist disappears:

'Twas right, said they, such birds to slay,

That bring the fog and mist.[3]—lines 101–102

They before long find that they fabricated a grave mistake in supporting this crime, as information technology arouses the wrath of spirits who then pursue the ship "from the land of mist and snow"; the south air current that had initially blown them north now sends the ship into uncharted waters near the equator, where it is becalmed:

Mean solar day after day, 24-hour interval after 24-hour interval,

Nosotros stuck, nor breath nor movement;

Every bit idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

H2o, water, every where,

Nor any driblet to drink.The very deep did rot: Oh Christ!

That always this should exist!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.[three]—lines 115–126

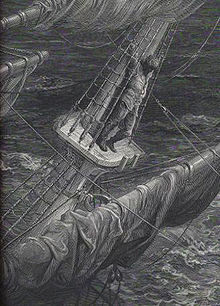

Engraving by Gustave Doré for an 1876 edition of the verse form. The Albatross depicts 17 sailors on the deck of a wooden ship facing an albatross. Icicles hang from the rigging.

The sailors change their minds again and blame the mariner for the torment of their thirst. In anger, the crew forces the mariner to wear the dead albatross well-nigh his neck, perhaps to illustrate the burden he must suffer from killing it, or perhaps as a sign of regret:

Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from sometime and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung.[3]—lines 139–142

After a "weary time", the ship encounters a ghostly hulk. On lath are Expiry (a skeleton) and the "Night-mare Life-in-Decease", a deathly stake woman, who are playing die for the souls of the crew. With a roll of the die, Death wins the lives of the coiffure members and Life-in-Decease the life of the mariner, a prize she considers more than valuable. Her name is a clue to the mariner's fate: he will suffer a fate worse than death as punishment for his killing of the albatross. I by i, all of the coiffure members die, but the mariner lives on, seeing for seven days and nights the curse in the optics of the coiffure'south corpses, whose last expressions remain upon their faces:

Four times l living men,

(And I heard nor sigh nor groan)

With heavy thump, a lifeless lump,

They dropped down ane past ane.The souls did from their bodies wing,—

They fled to bliss or woe!

And every soul, it passed me by,

Similar the whizz of my cross-bow![3]—lines 216–223

Eventually, this stage of the mariner'south curse is lifted after he begins to capeesh the many ocean creatures swimming in the water. Despite his cursing them as "slimy things" before in the poem, he suddenly sees their true dazzler and blesses them ("A jump of love gush'd from my heart, And I bless'd them unaware"). As he manages to pray, the albatross falls from his cervix and his guilt is partially expiated. Information technology and then starts to rain, and the bodies of the crew, possessed by adept spirits, ascension again and help steer the ship. In a trance, the mariner hears two spirits discussing his voyage and penance, and learns that the send is existence powered supernaturally:

The air is cut abroad before,

And closes from behind.[three]—lines 424–425

Finally the mariner wakes from his trance and comes in sight of his homeland, but is initially uncertain as to whether or non he is hallucinating:

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I encounter?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree?We drifted o'er the harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.[three]—lines 464–471

The rotten remains of the send sink in a whirlpool, leaving but the mariner behind. A hermit on the mainland who has spotted the approaching ship comes to meet it in a boat, rowed by a airplane pilot and his boy. When they pull the mariner from the water, they call up he is dead, but when he opens his mouth, the pilot shrieks with fear. The hermit prays, and the mariner picks up the oars to row. The pilot's male child laughs, thinking the mariner is the devil, and cries, "The Devil knows how to row". Back on land, the mariner is compelled by "a woful desperation" to tell the hermit his story.

Equally penance for shooting the boundness, the mariner, driven by the agony of his guilt, is at present forced to wander the earth, telling his story over and over, and pedagogy a lesson to those he meets:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small-scale;

For the dear God who loveth u.s.,

He made and loveth all.[3]—lines 614–617

After finishing his story, the mariner leaves, and the wedding-guest returns dwelling house, waking the adjacent morning "a sadder and a wiser man".

The verse form received mixed reviews from critics, and Coleridge was in one case told past the publisher that most of the volume'southward sales were to sailors who thought it was a naval songbook. Coleridge made several modifications to the poem over the years. In the second edition of Lyrical Ballads, published in 1800, he replaced many of the archaic words.

Inspiration for the poem [edit]

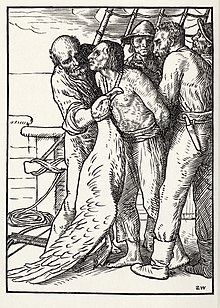

"The Albatross about my Cervix was Hung," etching past William Strang. Poem illustration published 1896.

The poem may accept been inspired by James Cook's second voyage of exploration (1772–1775) of the Southward Seas and the Pacific Ocean; Coleridge'southward tutor, William Wales, was the astronomer on Cook'south flagship and had a strong relationship with Melt. On this second voyage Melt crossed three times into the Antarctic Circle to decide whether the fabled great southern continent Terra Australis existed.[a] Critics have as well suggested that the poem may have been inspired by the voyage of Thomas James into the Arctic.[5]

According to Wordsworth, the poem was inspired while Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Wordsworth'south sister Dorothy were on a walking tour through the Quantock Hills in Somerset.[6] The discussion had turned to a book that Wordsworth was reading,[7] that described a privateering voyage in 1719 during which a melancholy sailor, Simon Hatley, shot a black albatross.[b]

Commemorative statue at Watchet, Somerset: the albatross hangs on a rope looped around the ancient mariner'southward neck.

"Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cantankerous, the Boundness

About my neck was hung."[3] : lines 139–142

As they discussed Shelvocke's book, Wordsworth proffered the following developmental critique to Coleridge, which importantly contains a reference to tutelary spirits: "Suppose you represent him as having killed one of these birds on entering the southward ocean, and the tutelary spirits of these regions accept upon them to avenge the criminal offence."[6] By the time the trio finished their walk, the poem had taken shape.

Bernard Martin argues in The Ancient Mariner and the Authentic Narrative that Coleridge was too influenced past the life of Anglican clergyman John Newton, who had a nearly-decease experience aboard a slave ship.[8]

The poem may also accept been inspired by the legends of the Wandering Jew, who was forced to wander the world until Judgement Day for a terrible crime, found in Charles Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer, Thou. Grand. Lewis' The Monk (a 1796 novel Coleridge reviewed), and the legend of the Flying Dutchman.[9] [10]

Information technology is argued that the harbour at Watchet in Somerset was the primary inspiration for the verse form, although some time before, John Cruikshank, a local associate of Coleridge'due south, had related a dream about a skeleton ship crewed by spectral sailors.[eleven] In September 2003, a commemorative statue, by Alan B. Herriot of Penicuik, Scotland, was unveiled at Watchet harbour.[12]

[edit]

In Biographia Literaria, Coleridge wrote:

The idea suggested itself (to which of united states I practise not recollect) that a series of poems might be composed of ii sorts. In the one, incidents and agents were to be, in part at least, supernatural, and the excellence aimed at was to consist in the interesting of the affections by the dramatic truth of such emotions, as would naturally accompany such situations, supposing them real. And existent in this sense they take been to every human being who, from whatever source of delusion, has at any time believed himself under supernatural agency. For the second class, subjects were to be chosen from ordinary life ... In this thought originated the plan of the Lyrical Ballads; in which it was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least Romantic; yet and then equally to transfer from our inwards nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing break of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith. ... With this view I wrote the Ancient Mariner.[13]

In Table Talk, Coleridge wrote:

Mrs. Barbauld once told me that she admired The Aboriginal Mariner very much, but that there were two faults in it – it was improbable, and had no moral. As for the probability, I owned that that might acknowledge some question; but as to the want of a moral, I told her that in my ain sentence the verse form had too much; and that the simply, or chief fault, if I might say then, was the obtrusion of the moral sentiment so openly on the reader as a principle or cause of action in a work of such pure imagination. It ought to take had no more moral than the Arabian Nights' tale of the merchant'south sitting down to eat dates past the side of a well, and throwing the shells bated, and lo! a genie starts up, and says he must kill the aforesaid merchant, because one of the engagement shells had, information technology seems, put out the eye of the genie'due south son.[14]

[edit]

Wordsworth wrote to Joseph Cottle in 1799:

From what I can get together it seems that the Ancient Mariner has upon the whole been an injury to the volume, I mean that the sometime words and the strangeness of it accept deterred readers from going on. If the volume should come to a second Edition I would put in its place some petty things which would be more likely to adapt the common taste.

Nevertheless, when Lyrical Ballads was reprinted, Wordsworth included it despite Coleridge's objections, writing:

The Verse form of my Friend has indeed bang-up defects; first, that the principal person has no distinct grapheme, either in his profession of Mariner, or as a man who having been long under the control of supernatural impressions might be supposed himself to partake of something supernatural; secondly, that he does not act, only is continually acted upon; thirdly, that the events having no necessary connection do non produce each other; and lastly, that the imagery is somewhat as well laboriously accumulated. Even so the Poem contains many fragile touches of passion, and indeed the passion is every where true to nature, a great number of the stanzas present beautiful images, and are expressed with unusual felicity of language; and the versification, though the metre is itself unfit for long poems, is harmonious and artfully varied, exhibiting the utmost powers of that metre, and every multifariousness of which information technology is capable. Information technology therefore appeared to me that these several claim (the first of which, namely that of the passion, is of the highest kind) gave to the Poem a value which is not often possessed past better Poems.

Early on criticisms [edit]

Upon its release, the poem was criticized for existence obscure and hard to read. The utilise of archaic spelling of words was seen as not in keeping with Wordsworth's claims of using common language. Criticism was renewed once again in 1815–1816, when Coleridge added marginal notes to the poem that were as well written in an archaic fashion. These notes or glosses, placed adjacent to the text of the poem, ostensibly interpret the verses much like marginal notes constitute in the Bible. At that place were many opinions on why Coleridge inserted the gloss.[15] Charles Lamb, who had deeply admired the original for its attention to "Homo Feeling", claimed that the gloss distanced the audience from the narrative, weakening the poem'southward effects. The entire verse form was start published in the collection of Lyrical Ballads. Another version of the poem was published in the 1817 collection entitled Sibylline Leaves (see 1817 in poetry).[sixteen]

Interpretations [edit]

On a surface level the poem explores a violation of nature and the resulting psychological effects on the mariner and on all those who hear him. According to Jerome McGann the poem is like a salvation story. The poem's structure is multi-layered text based on Coleridge's interest in higher criticism. "Like the Iliad or Paradise Lost or any dandy historical production, the Rime is a work of trans-historical rather than so-called universal significance. This verbal distinction is important because it calls attention to a real i. Similar The Divine Comedy or any other poem, the Rime is not valued or used ever or everywhere or by everyone in the aforementioned manner or for the same reasons."[17]

Whalley (1947)[xviii] suggests that the Aboriginal Mariner is an autobiographical portrait of Coleridge himself, comparing the mariner'due south loneliness with Coleridge'southward own feelings of loneliness expressed in his letters and journals.[18]

Versions of the verse form [edit]

Coleridge often fabricated changes to his poems and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was no exception – he produced at least eighteen different versions over the years.[19] (pp 128–130) He regarded revision as an essential function of creating verse.[xix] (p 138) The first published version of the poem was in Lyrical Ballads in 1798. The 2d edition of this anthology in 1800 included a revised text, requested past Coleridge, in which some of the linguistic communication and many of the archaic spellings were modernised. He also reduced the title to The Ancient Mariner simply for after versions the longer title was restored. The 1802 and 1805 editions of Lyrical Ballads had modest textual changes. In 1817 Coleridge's Sibylline Leaves album included a new version with an extensive marginal gloss, written past the poet. The terminal version he produced was in 1834.[20] [nineteen] (pp 127, 130, 134)

Traditionally literary critics regarded each revision of a text by an author every bit producing a more authoritative version and Coleridge published somewhat revised versions of the verse form in his Poetical Works anthology editions of 1828, 1829, and lastly in 1834 – the year of his decease. More recently scholars look to the earliest version, even in manuscript, as the most authoritative but for this poem no manuscript is extant. Hence the editors of the edition of Nerveless Poems published in 1972 used the 1798 version but made their ain modernisation of the spelling and they added some passages taken from later on editions.[19] (pp 128–129, 134)

The 1817 edition, the one most used today and the first to exist published under Coleridge's ain proper name rather than anonymously, added a new Latin epigraph but the major modify was the addition of the gloss that has a considerable effect on the way the poem reads.[21] (p 186) [22] [23] [19] (pp 130, 134) Coleridge's grandson Due east.H. Coleridge produced a detailed report of the published versions of the poem.[21] Over all, Coleridge's revisions resulted in the verse form losing 30-nine lines and an introductory prose "Argument", and gaining fifty-viii glosses and a Latin epigraph.[19] (p 134)

In general the anthologies included printed lists of errata and, in the example of the particularly lengthy list in Sibylline Leaves, the listing was included at the kickoff of the book. Such changes were often editorial rather than merely correcting errors.[19] (pp 131, 139) Coleridge also fabricated handwritten changes in printed volumes of his piece of work, peculiarly when he presented them as gifts to friends.[xix] (pp 134, 139)

In popular civilisation [edit]

In add-on to existence referred to in several other notable works, due to the popularity of the poem the phrase "boundness around ane'due south neck" has become an English-linguistic communication idiom referring to "a heavy brunt of guilt that becomes an obstacle to success".[24]

The phrase "Water, h2o, every where, / Nor whatsoever drop to potable" has appeared widely in popular civilization, just unremarkably given in a more natural modern phrasing as "Water, water, everywhere / Simply non a drop to drink"; some such appearances have, in turn, played on the frequency with which these lines are misquoted.[25]

Run into as well [edit]

- Albatross (metaphor)

Notes [edit]

- ^ "On 26 January 1774 he crossed into the Antarctic Circumvolve for the third time (having done so a second time the previous month) and 4 days subsequently, at 71°10' South, 106°54' W, accomplished his uttermost south."[4]

- ^ "We all observed, that nosotros had not the sight of one fish of any kind, since we were come to the Southward of the straits of le Mair, nor one sea-bird, except a disconsolate black Albatross, who accompanied the states for several days ... till Hattley, (my 2nd Helm) observing, in 1 of his melancholy fits, that this bird was always hovering near u.s., imagin'd, from his colour, that it might be some sick omen ... He, after some fruitless attempts, at length, shot the Albatross, not doubting we should have a fair air current after it."[7] [ page needed ]

References [edit]

- ^ "Revised version of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, published in Sibylline Leaves". The British Library . Retrieved i October 2019.

- ^ "The characteristics of romanticism institute in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner". pedagogy.seattlepi.com . Retrieved ane October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1921). Coleridge, E.H. (ed.). The Poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 186–209.

- ^ David, Andrew C.F. (January 2008) [2004]. "Cook, James (1728–1779)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford Academy Press.

- ^ Cooke, Alan (2000). "Thomas James". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Online ed.). Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ a b Coleridge, South.T. (1997). Keach, William (ed.). The Complete Poems / Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Penguin Books. pp. 498–499.

- ^ a b Shelvocke, George, Captain (1726). A Voyage Round The World by Fashion of the Great South Sea.

- ^ Martin, Bernard (1949). The Aboriginal Mariner and the Accurate Narrative. William Heinemann.

- ^ Fulmer, O. Bryan (Oct 1969). "The ancient mariner and the wandering jew". Studies in Philology. 66 (five): 797–815. JSTOR 4173656.

- ^ Clute, John; Grant, John, eds. (1999). The encyclopedia of fantasy. Macmillan. p. 210. ISBN978-0-312-19869-5.

- ^ "Samuel Taylor Coleridge". poetryfoundation.org. 11 December 2016. Retrieved 12 Dec 2016.

- ^ "Coleridge and Watchet". watchetmuseum.co.great britain. Watchet Museum. Retrieved 12 Dec 2016.

- ^ Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. "Chapter XIV". Biographia Literaria . Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ "TableTalks, p. 106". Archived from the original on xv April 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Wu, Duncan (1998). A Companion to Romanticism. Blackwell Publishing. p. 137. ISBN0-631-21877-seven.

- ^ "About The Rime of the Ancient Mariner". GradeSaver. Study Guide for The Rime of the Aboriginal Mariner.

- ^ McGann, Jerome J. (1985). The Beauty of Inflections. Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b Whalley, George (July 1947). "The mariner and the albatross". University of Toronto Quarterly. 16 (4): 381–398. doi:10.3138/utq.sixteen.four.381.

Reprinted in

Coburn, Kathleen, ed. (1967). Coleridge: A collection of critical essays . Prentice-Hall. - ^ a b c d e f g h Stillinger, Jack (1992). "The multiple versions of Coleridge'southward poems: How many Mariners did Coleridge write?". Studies in Romanticism. 31 (2): 127–146. doi:ten.2307/25600948. JSTOR 25600948.

- ^ Coleridge, S.T. (1836). The poetical works of S.T. Coleridge. Vol. II. London, UK: William Pickering. pp. one–27.

- ^ a b Coleridge, Due south.T. (1912). Coleridge, East.H. (ed.). The Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Vol. I. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Coleridge, Southward.T. (1912). Coleridge, E.H. (ed.). The Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Vol. Ii. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. - ^ Perry, Seamus (xv May 2014). "An introduction to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner". Discovering Literature: Romantics & Victorians. The British Library.

- ^ Jack, Belinda (21 February 2017). "Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and poetic technique". Gresham College. pp. 4, v, 10.

- ^ "albatross around one'south neck". Houghton Mifflin. 1997.

- ^ Merz, Theo (21 January 2014). "Ten literary quotes nosotros all get wrong". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

Sources [edit]

- Gardner, One thousand. The Annotated Ancient Mariner. New York, NY: Clarkson Potter, reprinted by Prometheus Books. ISBN1-59102-125-1.

- Lowes, J.L. (1927). The Road to Xanadu – a study in the ways of the imagination. Houghton Mifflin.

- Scott, Grant F. (2010). ""The many men so beautiful": Gustave Doré's illustrations to The Rime of the Ancient Mariner". Romanticism. xvi (1): 1–24.

External links [edit]

- Illustrations from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Gustave Doré illustrations from the University at Buffalo Libraries' Rare & Special Books collection

- The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, text from Projection Gutenberg

- The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, audiobook (Jane Aker) from Project Gutenberg

- The Rime of the Aboriginal Mariner : Critical Analysis and Summary

-

The Rime of the Aboriginal Mariner public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Rime of the Aboriginal Mariner public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Abstracts of literary criticism of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rime_of_the_Ancient_Mariner